Exploring our connection to the night sky from the World’s Largest International Dark Sky Sanctuary

Since the beginning of time the night sky has been an important part of life. Ancient cultures used it as a resource to guide them, predict the future, for accurate planting and harvesting, and to find answers to life's mysteries. It has inspired rituals, religions, science, philosophy, art, and cultural traditions. The night sky is an integral part of human heritage and is still important to us today. Many grow up learning about certain aspects of the sky, a fascination that often starts early with glow-in-the-dark star decals on bedroom ceilings and books about constellations. Our child-like wonder grows with each fact we learn. The expansive night sky becomes even more incredible when we discover it’s essentially the same sky people have been looking at for thousands of years. It gives us a broader view of what ties all of humanity together and how deeply connected we are to nature.

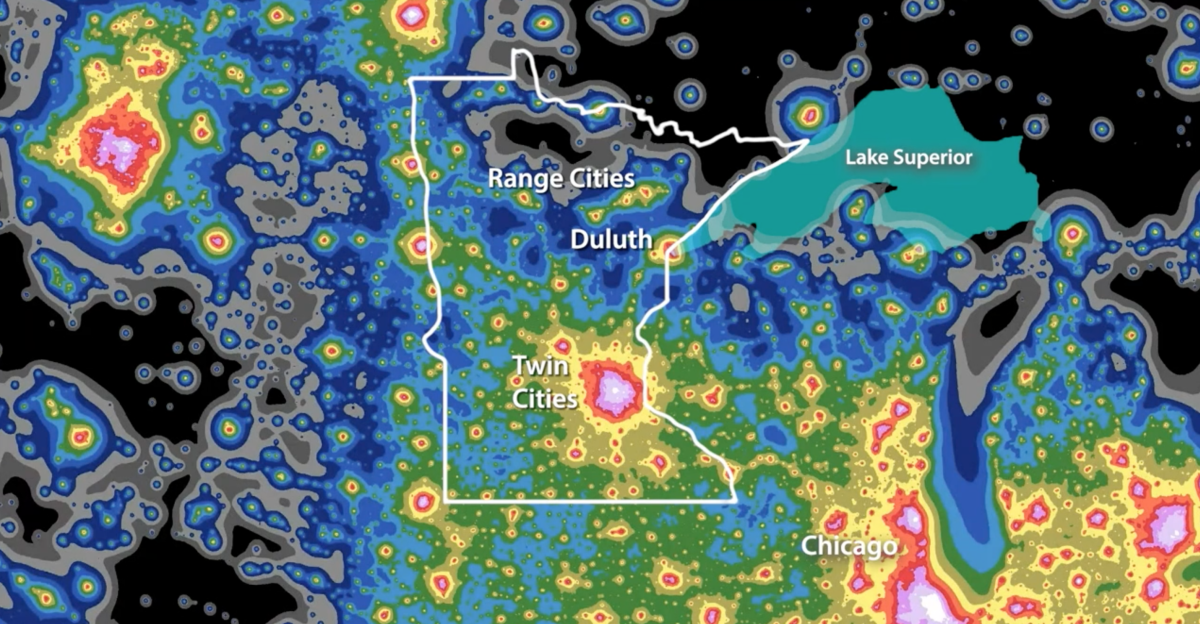

In Ely, we are lucky to live on the edge of the largest International Dark Sky Sanctuary in the world. In 2020, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness became only the 13th location to earn this designation, by the International Dark Sky Association. The IDA is a nonprofit organization working to protect the night sky using education, advocacy, and science. The nearly 1.1 million acre BWCAW is the first designated site in Minnesota and became the first federally designated wilderness site in the US. People have been coming to the BWCAW for years to experience the wilderness and starry skies. It’s no surprise that most who live in or near cities rarely get to see a clear view of the stars. The glow from lights in urban areas can travel for hundreds of miles. Night sky expert Paul Bogard, author of The End of Night, says that 8 out of 10 kids born in the US will never live where they can see the Milky Way, once one of the most common human experiences. Making our nights less dark negatively impacts human health, global energy efficiency, and interrupts wildlife patterns, especially bird migration. Excess light harms trees, fish, plant pollination, and insect activity. This is why we must work to make our nights darker and protect our dark sky places from light pollution.

Still from the film "Northern Nights, Starry Skies"

Half of the light pollution comes from street lamps, while another third is parking lot lights that stay on even when no one is using them. While many cities are working to minimize excess light with lower Kelvin lighting (a unit used to measure the color temperature of a lightbulb), the BWCAW is already a refuge for those seeking dark skies. Sitting at a campsite or in a canoe in the middle of the lake, one only needs to look up to see an incredible view without a telescope. This can also be experienced in the many campgrounds outside of the BWCAW, near Ely. People see stars, meteors, planets, the Milky Way, and constellations in a way that wouldn’t be possible in other places. The clarity of the view makes it easier to understand the inspiration of those who came before us, especially the Anishinaabe people who have always had a special relationship with the land, water, and night sky in what is now known as the BWCAW.

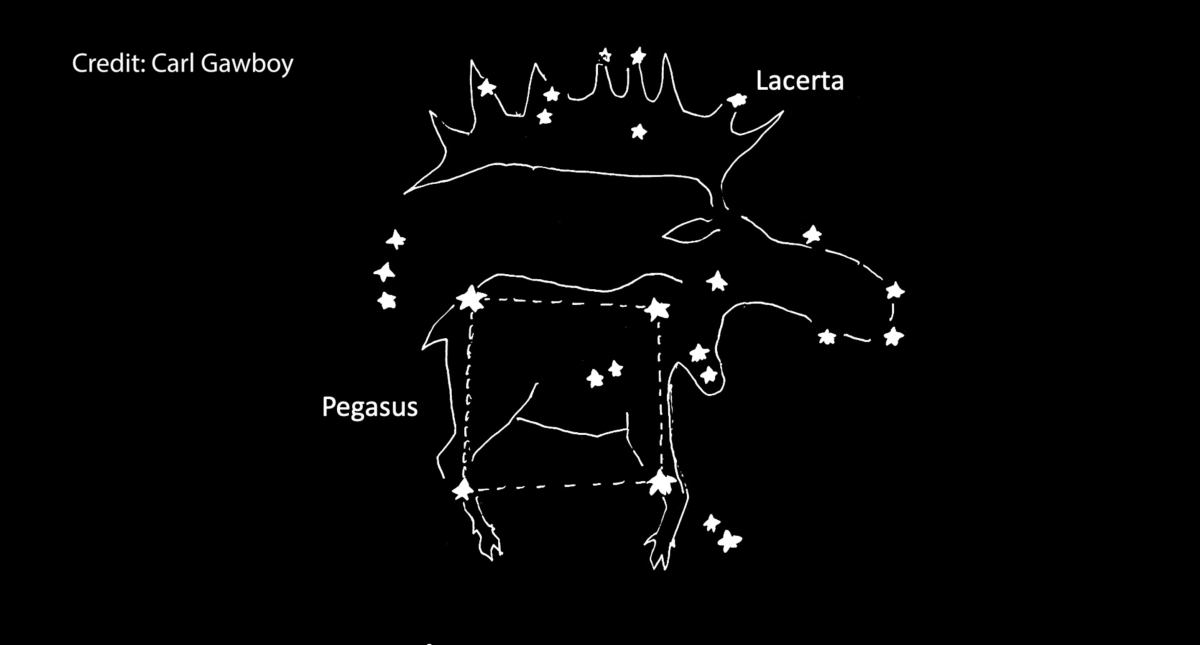

Still from the film "Northern Nights, Starry Skies", credit to Carl Gawboy

Ojibwe tribes use constellations for important references like the changing of seasons and to tell stories. Anyone who has peered at one of the lakes at night can see how the night sky reflected in the water ties the two together as one. It’s why many Native American tribes believe we come from the stars and to the stars we will return. According to Carl Gawboy, an Ojibwe artist—for the Ojibwe people, the Milky Way (Jiibay Ziibi) is known as the River of Souls where people embark in a canoe into the afterlife. Minnesota gets its name from the Dakota phrase Mni Sóta Makoce, or “the land where the water reflects the sky.” Standing on the shore at night, one will see the stars in the lake making it impossible to see where one ends and one begins. It’s an incredible experience.

Scientists have confirmed what many cultures have believed all along; we are all intricately connected to the night sky. The same atoms that make up the stars are in us too; we are essentially made of stardust. Dark skies are important to the well-being of humans and the proper functioning of the ecosystem. Ely offers a place where people can easily access the night sky without interference from light. It’s a chance to honor those who came before us for their wisdom, reminding us of our relationship with all living things. Another bonus is the incredible display of Northern Lights that are visible close to town. Astrotourism is gaining in popularity, with the BWCAW becoming a favored destination for it. Many have a goal of seeing the Aurora Borealis and there’s no better place than right outside of Ely, Minnesota.

We all can make a difference when it comes to protecting the night sky with star-friendly lighting and advocacy. This will ensure that future generations can also benefit from dark skies, get to be inspired by all that the stars offer, and see their place in our connected universe.

We all can make a difference when it comes to protecting the night sky with star-friendly lighting and advocacy. This will ensure that future generations can also benefit from dark skies, get to be inspired by all that the stars offer, and see their place in our connected universe.

Still from the film "Northern Nights, Starry Skies"

“I look up at the night sky and I know that, yes, we are part of this Universe, we are in this Universe, but perhaps more important than both of those facts is that the Universe is in us. When I reflect on that fact, I look up—many people feel small, because they’re small and the Universe is big, but I feel big, because my atoms came from those stars.”

― Neil deGrasse Tyson

References / Learn More:

Northern Nights, Starry Skies | PBS

DarkSky International | Protecting the night skies for present and future generations

DarkSky International | Effects of Light Pollution on Human Health